Banana varieties beyond the yellow banana

Did you know that there are more than a thousand varieties of banana in the world? In Europe, we usually only know one: the sweet yellow banana – the Canarian banana, or Cavendish.

The banana travelled around the world before reaching America. The plant is native to the Indomalayan region, from where it spread to Africa and the Mediterranean, and crossed the Atlantic via the Canary Islands around 1516. Curiously, in Europe we settled on the sweetest and most domesticated variety, without giving the banana tree’s many other forms a chance.

To each their own banana

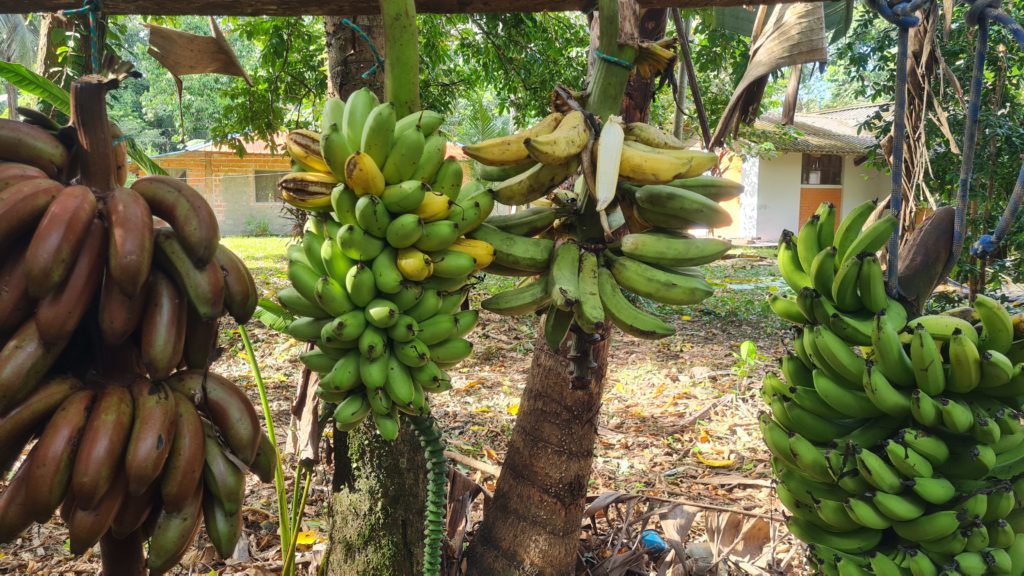

As we travel across the continent, we learn that each country has a different name for them. We have tried verdes, maduros, guineos, oritos, plantains, and even red bananas.

There is also no lack of diversity in how they are prepared: fried or roasted, patacones or tostones (double-fried plantain), bolones (plantain and cheese balls), green tortillas, chifles (chips), boiled plantain and as many other versions as you can imagine!

I love patacones or tostones – in Venezuela, patacones are hamburgers with tostones, and Colombian patacones are tostones. Why make it easy? On the other hand, I confess that boiled green plantains or plantain soup don’t win me over: they’re too bland.

In many countries, sweet bananas are hardly ever used outside of desserts. The one that reigns supreme in kitchens is the plantain, which is as versatile as the potato.

Let’s get things straight with Spanish names

According to the RAE (Spanish Dictionary), plátano refers to both the plant of the Musaceae family and its fruit, and considers banano and banana to be synonyms. But in practice, the names change depending on the region:

Banano or banano: the ripe, sweet, raw-edible fruit. In the south of South America, it is called banana; in Central America and Colombia, banano; in Venezuela, cambur; in Ecuador, orito for small ones. Or also guineo is heard across the Latin region.

Cooking bananas, as plantains are also called, are starchier, so they have to be cooked or fried before serving. They’re called verde (green plantain), macho (male) or plátano grande (big plantain). When plantains ripe, then thy’re called maduros – that is ripe in Spanish.

A touch of colour

Beyond the classic yellow, there are curious varieties such as the red or silk banana, which has a sweet flavour with hints of raspberry and a high beta-carotene content that gives the skin its characteristic colour. We tried it in Bolivia, and along with the orito, it’s one of my favourites.

There is also the apple banana, with a flavour reminiscent of the green fruit; I still have that one to try.

The banana market, a global giant

Bananas from the Canary Islands are the mainstay of European supermarkets, along with those from the Azores and the French Caribbean territories. However, domestic production only covers 11% of demand. The rest is supplied from abroad, with 74% of imports coming from Latin America, almost 4.3 million tonnes in 2021.

Ecuador, Colombia and Costa Rica are the main exporters to Europe, a reality that is very much in evidence throughout our trip. Banana trees can be found on every corner and in every garden, and every house has a bunch of green bananas hanging under the porch, ready to be used. And millions of fruit flies as soon as the odd one ripens too much.

Exports focus on bananas, still green, and less on plantains. The latter remains a niche product of immigrant kitchens in Europe.

Behind the flavour: banana companies

Between Panama and Costa Rica, there are large plantations of bananas for export. It is a monotonous and boring landscape, interrupted by mechanised steps to transport the bunches, but little else. In Panama, we also passed through plantations rotting due to mass layoffs by the American banana giant Chiquita.

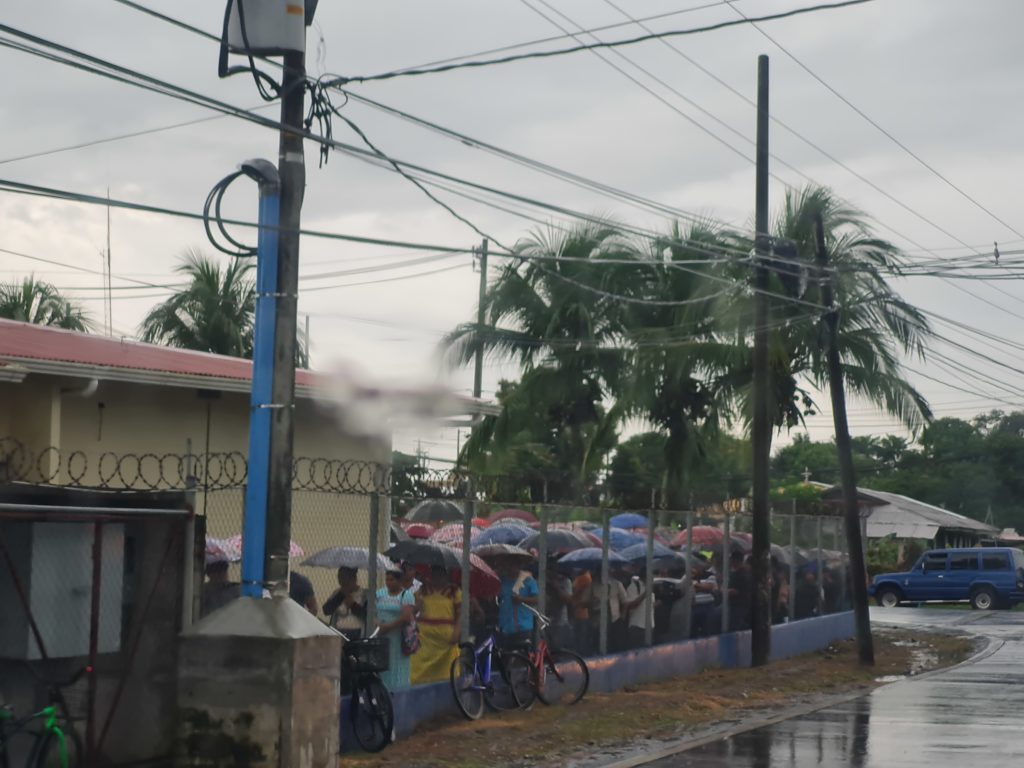

As is common in the agricultural sector, banana workers also labour in minimal conditions, although in this case the workers went on strike due to changes in national retirement laws. For not showing up to work, Chiquita dismissed its entire workforce of five thousand workers; obviously, the plantations were abandoned. Even so, Chiquita does not want to lose money and has announced that it will return to Panama in February 2026 following an agreement with the Panamanian government. In the meantime, the bananas rot and the banana workers queue in the rain outside the employment office.

The plague that leads to another

The Cavendish banana, now ubiquitous, replaced the old Gros Michel, which was wiped out by the Panama disease, a fungal plague.

Now, a new strain of the fungus threatens plantations, while in countries such as Ecuador, Moko, a bacterium, affects both plantains and bananas.

The plátano tree is a delicate plant with many enemies, which is why plantations are heavily sprayed. This is often done by aerial spraying with light aircraft or, more recently, with drones, which allow agrochemicals to be spread with greater precision.

We are impressed by the variety of plantains and bananas and their use in cooking. No one can take away my patacones or the occasional fried ripe plantain, but I will have to see where I can find them in Europe and, maybe one day, even buy some that are not just yellow.

Which ones have you tried?